MotM EXCLUSIVE | Going Homeless In Gran Ghetto

The exposed trash heap and clothing vendors at the back of Gran Ghetto. Foggia, Italy. 8 October 2019. ©Pamela Kerpius

16 October 2019

by Pamela Kerpius

Introduction

“Just say ‘ghetto’ and anyone will tell you what bus to take. Just say ‘ghetto.’”

Peter* (Sierra Leone) told me this again and again in the days leading up to my visit. Those are imprecise, if not outright dubious directions when you’re wondering how to meet someone in one of Italy’s most precarious places.

Peter is in a ghetto in Foggia, Italy after leaving Isernia, a small town in the Molise region where I first met him in spring of this year. He had been living there for three years after his rescue at sea and first reception in Sicily, in October 2016.

The asylum process took that entire time to initiate and conclude; and in the meantime, he was living in a converted apartment complex in Isernia, just one among many of Italy’s temporary housing centers for migrants. His asylum hearing came back negative the first time, he appealed, but when the appeal came back negative too, he was asked to leave the housing center once and for all.

On one of the final days before Peter went homeless in September 2019, we met in Isernia to record his journey story for the archive and a conversation for the Open Encounters podcast.

We knew his homelessness was impending, it was a matter of waiting for Questura, police headquarters, to send down the formal paperwork. We knew also that he would head to Foggia, where there was guaranteed work to harvest vegetables in the agricultural fields that are ubiquitous and expansive there in the Puglia region.

We knew too he would stay in a ghetto. There are multiple ghettos outside Foggia, each that are infamous for their poor conditions.** So it was no surprise the indignity Peter would face when he arrived.

Except that it was. Because we are human, there is no amount of mental preparation one can do to equip himself for a life on the margins and in squalor.

I told Peter I would visit and he promised to escort me through this dangerous place that few on the outside have seen first-hand.

That place is Gran Ghetto, the worst of the region’s ghettos and one that has been around for decades. Hundreds if not thousands of migrants, documented and not, inhabit the ghettos here over the flux of the high and low agricultural seasons.

It is all part of a migrant labor exploitation system that keeps these most vulnerable of people powerless and pinned to a field for scant wages when there is no other work available for them; and cramped in deplorable, unsanitary living conditions that are directly tied to Italy’s agricultural economy.

The experience of traveling to and entering Gran Ghetto is uncomfortable and precarious as to be uncanny.

The teetering bus charging over broken, abandoned roads, the mountains of refuse surrounding the ghetto’s grounds, the feral animals inside darting over mud puddles and picking at trash, the smell of kerosene gas, rotting waste and urine that come and go with the wind––these are some of the horrifying characteristics. But there is one worse, and it’s the anger latent in the air of humans having been forced to believe that they are no more valuable than this.

Gran Ghetto is humanity discounted, and because it is so removed from sight, we can say moreover, humanity discarded.

Understand the rules to start: I was not wanted there. I came on arrival with a camera, which, discreet as it may have been, and as ethically as I tried to capture the grounds and the people in its frame, no one in Gran Ghetto is proud of being there and does not wish to have its undignified realities revealed.

This territorial instinct we might understand as a final bastion against its people’s outright erasure of self-worth: that is to say, if no one can see how they live, they cannot be associated with its fundamental humiliation.

“Pretend you’re playing a video game,” Peter told me as I tried to capture photos and videos. Many inevitably begin pointed at the ground. I ask your patience; there is a look to be had, it will take a few frames to get there.

All photos and videos were taken with careful discretion to protect my personal security as well, and beyond the visit, the security of Peter and some of the others who allowed me into their lives. Consider a look at the coverage not as a privileged glance inside, rather, as a mirror of our collective complicity.

Here, the first-person report and a look inside the rarely-seen Gran Ghetto from the MotM visit in October 2019.

Off The Grid: Homeless migrants on the way to Gran Ghetto. Foggia, Italy; 8 October 2019. ©Pamela Kerpius

“Come, come in,” Peter said, ushering me hurriedly indoors.

He kicked his shoes off on the muddy shipping pallet that subs as the porch step at the entryway to his home. He lives in a dilapidated mobile trailer unit, the kind you’d hitch to the back of a truck for an extended road trip––just big enough to hold two beds snugly––but here in Gran Ghetto, the squalid off-the-grid camp in Foggia, Italy where migrants are put strategically to be forgotten, they just call them “containers.”

Words matter. And in this instance, the phrasing fits, because all this place does––true to its word––is contain the five people who inhabit it. A real home gives you space to stretch and relax into yourself. A container only holds you in place.

This container has a makeshift stove connected to a leaky kerosene tank that leaves a worrisomely strong odor in the air. When I walked into this part of the camp the smell of gas was marked. Powerful enough that in any other circumstance I’d have evacuated and called immediately for emergency repair. But normal procedures of society do not apply here. You’re at the mercy of Gran Ghetto’s negligible resources.

The cooking stove is flush with the foot of Peter’s bed, a double-sized mattress that he shares with two others. That makes for three grown men to a bed a night. On the opposite side, the next double bed is penned in by the front door and a tiny closet, two sleep here; leaving behind a rectangular patch of standing room-only in between. Zero privacy. The whole area––the kitchen, bedroom, changing room––is all wrapped into one.

I’m struck by the habit we have of domesticating even the most uninhabitable of spaces to help find the peace of routine. The rate, Peter says, for this fragment of space is about 100 euros per person for a six month stay.

His roommate inside is making tea, a bitter brew sweetened with white sugar. He’s distributed it among clear glass espresso cups atop an aluminum tray and offers one to me. I slip my sneakers off and place them on the muddy slats, and step inside.

The floor is clean inside. Everything else is broken, used, dilapidated, scratched, charred or faded––including the walls, the tiny countertop, the bedsheets. But the floor is diligently kept clean. It’s an act of dignity by way of the self-enforced no-shoe rule he and his roommates keep, and one tantamount to high ceremony in these parts where there is no innate opportunity for it.

I take the tea with a grazie.

I speak English with Peter, his native tongue, but Italian with the guys inside who are all from French-speaking Conakry, Guinea. Even when we all only speak mixed-level Italian, it remains our best language in common.

In fact, what we speak isn’t true Italian at all, but a jumbled mix of commands, mis-conjugated verbs, and clever slang names. Still, these words matter.

“Ehi, capo,” bossman. There’s a word for it no matter where you go, and especially, perhaps, in places where no one has power.

Everyone here is boss to Peter, neighbors who he greets with “capo” across the ghetto’s coarse streets, a palliative I think he uses to temper suspicions of me quietly trailing his side with a camera. I’m not supposed to be here, and when anyone notices me snapping pictures they make it clear to stop. I was being watched. Even stretches of street that looked evacuated would suddenly ring out with a warning call.

Sometimes people passing would command in Italian, “Non fare video,” don’t take video, but more often than not it was a larger motion, a codified holler that let everyone in the vicinity know of an intruder.

Peter acted natural, looked ahead, murmured a few “Ehi, capo’s” again, and told me just to put the camera away for now. Later, beside the expanse of an exposed trash pile that looks like an open landfill at the back of the camp, he’d direct my shots. He’d tell me to take my phone quickly and pass around 360-degrees then stop. He’d tell me at other times to pretend I was playing a video game on my phone––just don’t make it look like you’re shooting anything.

In front of the exposed mountain of trash is a spread of vendors, Roma immigrants, I think, selling used clothes and shoes, and random housewares, even a flatscreen TV I saw propped beside one tarp, although there is no electrical service to the ghetto. Peter says the people here buy up the clothes and mail them back to family in Africa. One vendor tried to sell me a blue handbag for two euros. All around there is mud. Gloppy puddles accumulated from the downpour the day before, and there is a veritable parking lot of cars.

There are actually cars everywhere lining the path of the camp, more cars, it seemed, than containers. Some people sleep in them. They belong to the unlicensed taxi drivers who take others to Foggia central or make transfers to the agricultural fields for work for a few euros. It is five euros a person from the camp to the city, which traverses a long road to the principle road beyond––in itself a long, isolated stretch, gutted with potholes––that winds and weaves through the abandoned farm fields until you start to reach the traffic of central Foggia.

Elapsed footage from Gran Ghetto to Foggia to show just how far afield it lies. 8 October 2019. ©Pamela Kerpius

Back on the streets inside the camp though, if we call them paved, it would merely be by dried mud. They’ve been dried, jaggedly shifted and compacted so many times amidst jutting stones that Peter and I do well if we don’t twist an ankle on our way through the maze of containers and corrugated metal shacks.

The road around the ghetto is, anyway, built to bring you to a halt, trip you up, not guide you to a destination intrinsically. And, of course, on the day I visited we were limited even more for the mud puddles that accumulated from the rain. Mucky grooves in any valley of the ground’s pocked surface. The rain also put everyone on furlough from their fieldwork the day before, and for Peter and others, on this day too.

That time off matters. Now, at the low season, Peter is only working five or 6 hours a day, cutting the usual salary in half. At the very peak of the summer season, migrants will sieve through the fields under the intense southern sun for up to eleven or 12 hours at a stretch. Some have reported earning as little as 4 euros an hour**; Peter earns five.

Most are picking tomatoes and zucchini, lately is also a season for asparagus, which Peter said he had been harvesting by hand with a knife, standing and slung over for hours. He complains of backache, like everyone else here who does this work. On the long road into the ghetto, a cluster of workers were hunched over severing plants from the adjacent marijuana field. Amadou* a twenty-year-old from Guinea, complained about his back too, shaking his head as if to say you just can’t know unless you’ve tried. He operates a mobile phone repair shop from a found bedside table, it’s his storefront facing the edge of the camp, a side gig, but nothing sustainable.

All of this is leaving marks. There is a deep line across the cuticle of one of Peter’s fingers, a scar from a misplaced stroke of a knife in the asparagus field. Everyone I ask about the work splays their palms out in reply to show the enormous blisters they’ve acquired from it. Peter says he is unwell. He says his skin does not look the same, its color is off, that his body, too, has a different shape.

These are marks in the most literal sense, even if the latter of the two Peter described are imperceptible to me, and even if he appears as fit and trim as I remember him a few weeks ago when he was still in Isernia. Instead, it was the pale abrasion of his voice that suggested a deformity too insidious to see. Fresh air may be abundant in the wide farm fields surrounding Gran Ghetto, but inside a poison lingers that you can’t seem to exhale.

You can point, again, in literal terms to the car fumes for that, and to the smoke wafting from tiny fires people put up in metal cans. A man was cooking meat directly atop a fire log on one.

But the irritants are immaterial too, weighted and asphyxiating. I think what Peter was talking about when he described the differences he observed in himself lie in the routine of being in Gran Ghetto with no end in sight.

He knows every day he will wake up in a cramped bed with no privacy. Since there are no toilets, he will walk to the adjacent field to urinate or defecate when he has to. His steps will teeter over the broken road dodging trash, hazards and rotting scraps. He’ll watch filthy feral animals scout the streets as if they have as much territorial right. He will wash in a makeshift shower with cold water. He’ll keep an eye out for characters he does not trust. He will climb aboard a car from an unlicensed driver to take him to work in a field, and pay him 5 euros for the service––what amounts to 20% of what his salary will be that day. He will harvest for hours in the open with no gloves and hope that he does not injure himself. And when it’s all over, he’ll return to the muddy streets, the feral animals, the suspicious neighbors and wonder how any of this could be real in a place of promise that he fought so extraordinarily hard to find. That night, he will climb back into the cramped bed and hope to sleep among his randomly inherited roommates in five. He will lie in the dark, stiff and silent, and very neatly contained.

It was clear the pain, fear and sheer precariousness of being here had sunk into tissue much deeper than Peter’s obvious physical self.

It was the impact of the bigger suffering yet of knowing that beyond the staggering reconciliation he has to make with this place as a reflection of his own identity, still, no one would be there to acknowledge his humiliation as real. There is something worse than indignity and it is the world altogether ignoring your existence.

It is the careful orchestration of governmental procedures on this diminutive plot that are exactly designed to avoid acknowledging its people exist.

Gran Ghetto by name is not on the map.

Formerly it was known as Gran Ghetto di Rignano Garganico, Rignano Garganico the city beyond it in the foothills that lays claim to this area; by virtue of its geography Gran Ghetto fell under its jurisdiction. But it is bad marketing to have a ghetto associated with your city. The mayor had its name taken off, making Gran Ghetto (di Rignano Garganico) administratively-speaking closed, chiuso. No name, no existence.

Words matter. At the head of the camp there is a sign instead that reads, “Località Torretta Antonacci” that ticks the bureaucratic box of making it an official location (località) without accounting for the type of location everyone knows it is, a ghetto. Torretta Antonacci is simply the historical name of this part of the countryside.

In any case, Peter carries on. His clothes are fresh and neatly pressed. There is still a conscious expression to his style––a ball cap he wears, the bag over his shoulder––much more so than others I notice who have been around the ghetto longer. He’s only been there a few weeks. Some, have been there for years.

A mentality of normalcy sets in by then, and it is principally why I suspect the other crucial reason people do not want pictures of this place exposed is for one in direct opposition to their existence being recognized in a moment of shame.

For a population already pushed to the margins, exploited, seen as a burden and an invading enemy; for people who are disliked for their skin color, who have had their dignity stripped and any stable, integrated role in society removed, all they have left is this place where the world can’t see them to disenfranchise them any further. If it goes away, what have they got left?

I met Amadou who showed me his cell phone repair stand, of course. But there is a barbershop too (I was warned not to take a picture of it), a market, a small street restaurant. Some of Peter’s roommates put out a tarp of their own to sell used clothes that they pick up in bulk in the city––these, all the elements of a self-contained community. They have built it under the worst of circumstances when no one would see them. So to put light on it for the very outsiders who inaugurated its structure of indignity undermines the efforts at survival for the people inside.

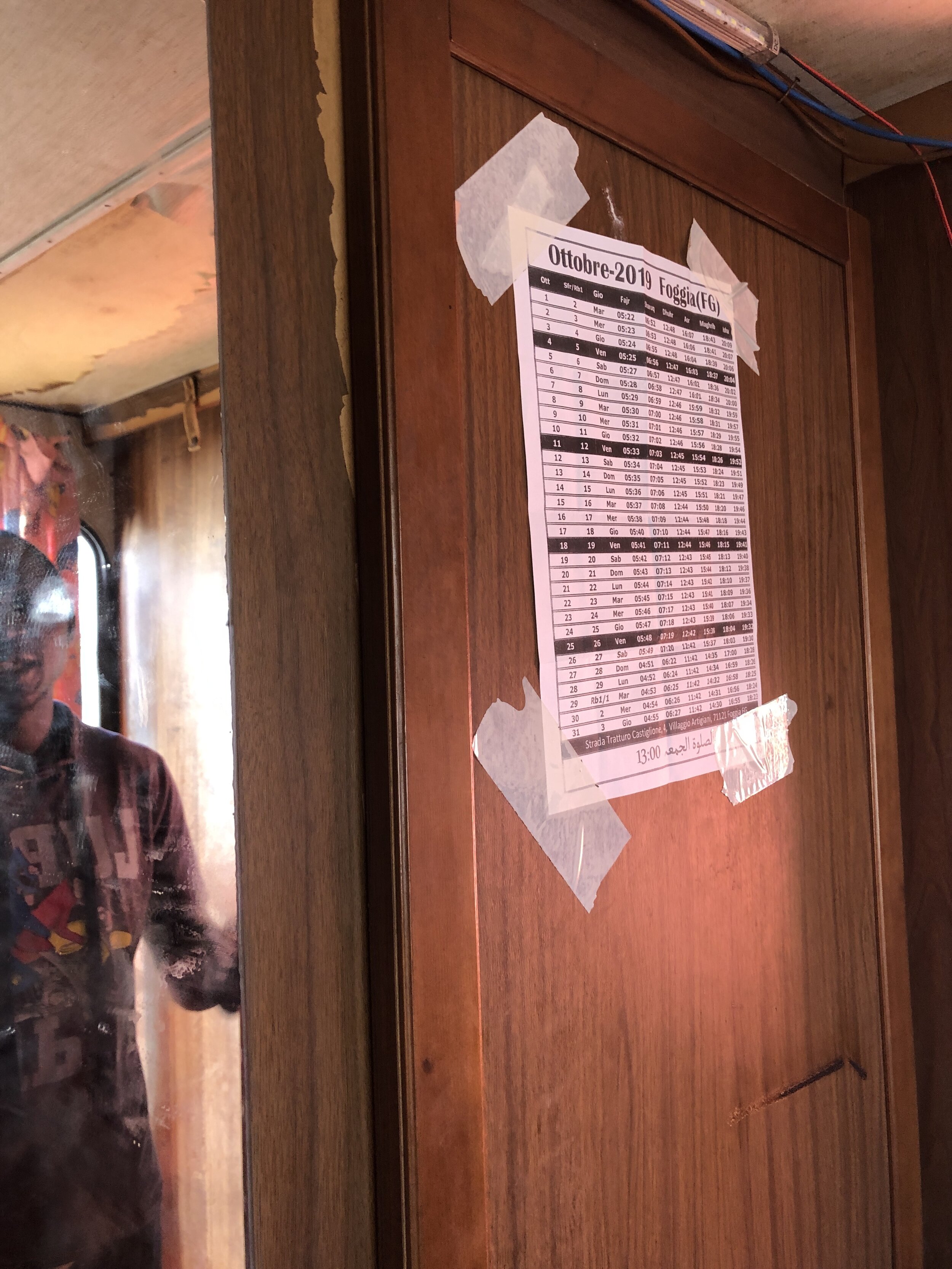

Peter and his roommate keep a calendar taped to the wall of their container. They are keeping track of the days, they have a sense of time and autonomy even if the world outside thinks they don’t.

After being out there in Gran Ghetto, on the concealed plot serviced by fractured roads and impassible ones within, and hiding away in its human containers, the distance from it now feels a bit like a baby putting her hands over her eyes and saying, can’t see me.

Basically, like an abject denial of reality, much less, humanity.

Inside the notorious migrant ghetto in Foggia, Italy. 8 October 2019. ©Pamela Kerpius

Read Peter’s original journey story, recorded September 2019 >

Listen to Part I of Peter’s conversation for Open Encounters >

* Name has been changed for security.

** MotM reported on this last year from the inside of the Borgo Mezzanone ghetto that is directly adjacent to the fence of the Italian government’s formal migrant reception center, using photographs provided by a Gambian man we follow living there.